At the end of The Fire Next Time, James Baldwin explains what needs to happen in America to end the effects of white supremacy: "If we - and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others - do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world. If we do not dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophesy, re-created from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!" With white supremacy now burning out in the open, fed by white resentment of the economic and political achievements of non- whites, all Americans must not falter in their duty to end our racial nightmare.

Full Scale /

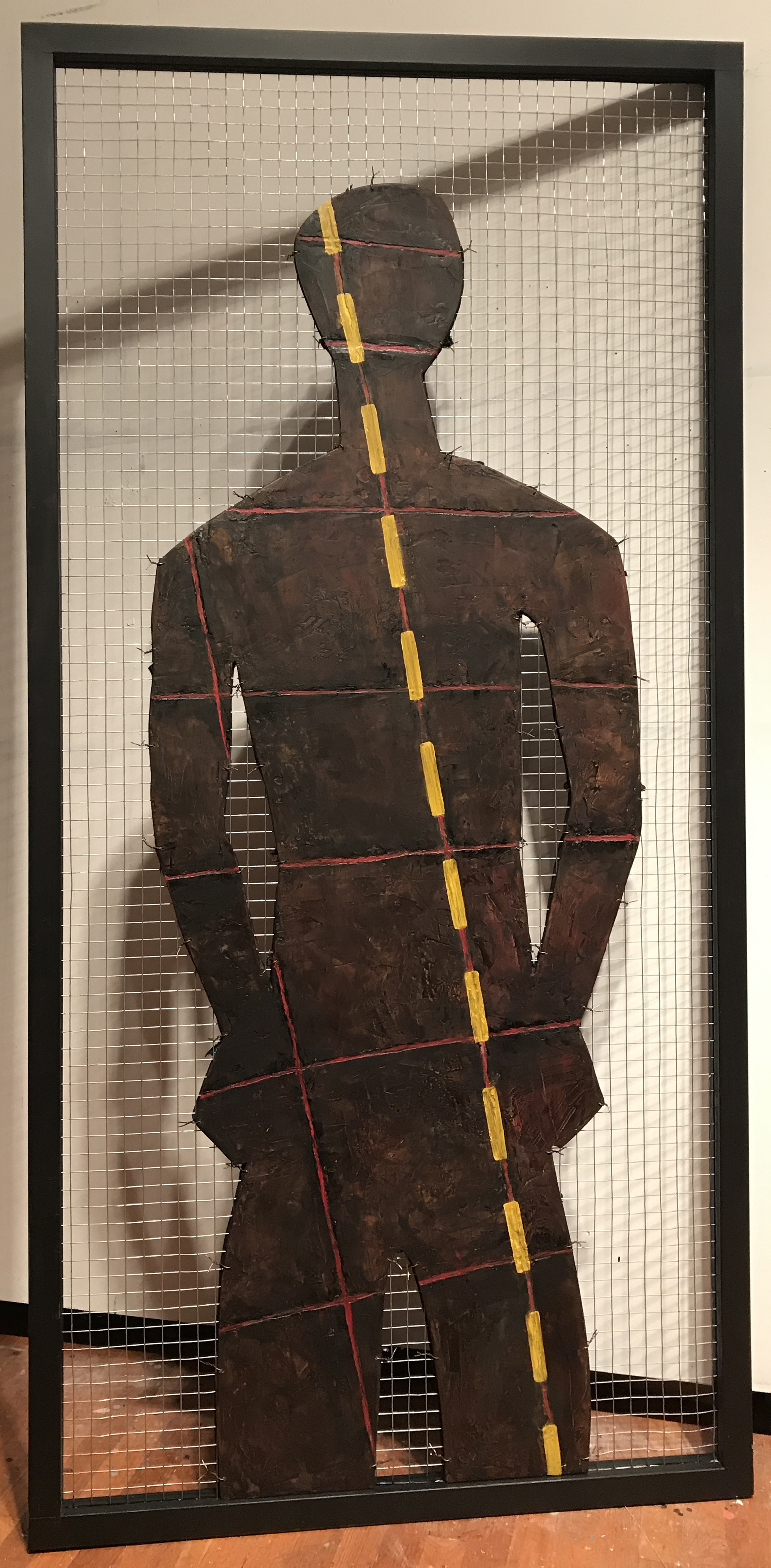

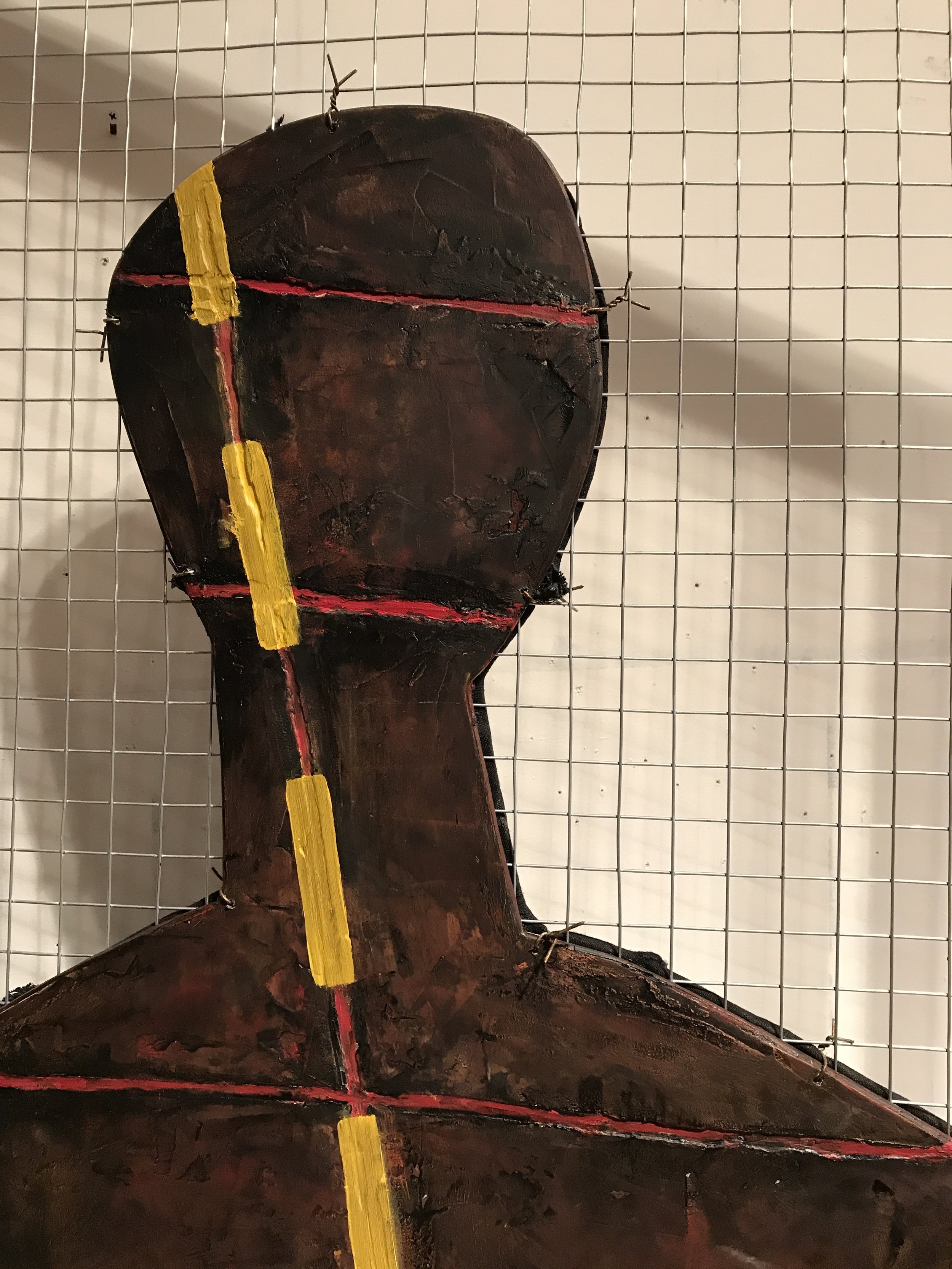

I’ve begun making full scale pieces of Keep the Top Eye Open. One, “Body/Target” originally was going to be just a reproduction of a gun target. But when I looked up “paper gun targets” I was astounded that most of them were black silhouettes with white scoring lines. Proportionally, very few of those for sale are white paper with black concentric lines.

I wanted to take the idea of a shooting target and transform it into a panel that I could use in the part of the installation that expressed the torture methods used by enslavers to break black bodies and minds. So I maintained the basic trope of full frontal with hands in fists by the side but redrew the image. I also built the padded figure out of roughly sewn sections, since one of the most elided aspects of American enslavement was the continual and casual fracturing of enslaved families - and hence individuals.

William Still, son of a fugitive mother and head of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee returned his diaries of escaped slaves to burial in a nearby cemetery every night. Even though his own life, the life of other enablers, and the lives of escaped slaves would be in jeopardy if the diaries were found, he kept them because he knew that his diaries might be the only way family members could later find each other. Every escaped slave took an alias upon leaving his or her forced labor camp. So anyone coming after would not be able to discover where a father, husband, sister, mother, had gone if no one kept a record of their original name; where the fugitive came from; who had been their enslaver; where they were headed; and what they would now be called. After the Civil War William Still published his diaries in hopes that freed men and women might be able to find some of their relatives.

The second panel, “The Past of this American Present: I” is self-explanatory.

Hineni: Here I am /

During Rosh Hashanah services the prayer leader chants a personal entreaty that begins, “Hineni”. By using that one word we are reminded of Abraham’s response when God calls on him to sacrifice his only son: Here I am. The cantor, who prays both with and for the whole congregation, uses this prayer to beg God to recognize that he or she was chosen because of the beauty of their voice; any unworthiness are his or hers alone; and to ask God to cover the transgressions of the congregation with love.

I have always cherished this prayer. I don’t know how wonderful my artistic voice might be. But I want use my voice to understand how we are deeply, emotionally and unconsciously driven by this country’s fraught creation story. America’s past will continue to violate our most hopeful and kind desires for unity and equality unless white people join black people to directly confront the ruinous effects of white supremacy on all our social and economic interactions.

I am here. Hopefully my art will add some understanding to the past of this American present.

Whitelash /

America doesn’t like to look back. The future is part of our cultural DNA. Our collective wish to forge forward hides how our past enslavement of people with black skin by people born with white skin affects our present. We, especially white people who imagine human equality, thought that with the passage of Civil Rights legislation and the ending Jim Crow, the arc of history’s inexorable bending towards justice and equality would continue into the indefinite future.

Today we find ourselves in a second major whitelash against the social, political and economic gains of black and brown Americans. The first was the undoing of Reconstruction and the imposition of Jim Crow after Emancipation. Those same forces of privileged resentment now want to wipe out the gains of the Civil Rights movement that culminated in the election of a black president.

I thought that resentment could never again be part of our national discourse, much less guide government policy. Turns out that the effects of the brutal practices of our white supremacist past still linger in this American present. This movement song got it right: “Freedom is a hard-won thing. You’ve got to work for it, fight for it, day and night for it, and every generation’s got to win it again.” Until we have again bent the arc of history so it heads again towards equality and justice all other aesthetic concerns seem to me insignificant.